How Lucknow Graced the World, With Ustad ji

Natalia Hildner

The performing arts are perhaps one of the last pretexts where the width and the depth of our subconscious can unleash themselves without fear of censure. While our day-to-day interactions must conform to the pressures and expectations of our present socio-economic realities, the arts hold a unique standing due to their ability to express human thought and sentiment according to their own subjective logic. In our past, the performing arts have often served as a means of bringing people together as a community, as a means of divine worship and ceremonies, as a means of honoring different aspects of human life, and several other real-world purposes. Today, however, though art may be popular within certain metropolitan spheres as entertainment, there are no specific practical assigned roles for art in daily life. Plainly put: the contemporary person believes, that even if we don’t perform the rain dance, scientifically, the rain will still come or not come. However, do we really know the effects of not having dance and music in our lives, scientifically, physically, mentally, and socially? Or more importantly, ever since we stopped dancing for the rain, do we still care as much about its coming or going? The point is not to start dancing for the rain, but to become conscious of the fact that performing arts are now considered an extracurricular or supplementary activity, disengaged and disconnected from reality. Trying to fill that same void, advertisements and virtual media produced by anonymous others increasingly fill every corner of our lives using their creativity as a means of trying to sell us something. While the desires and dreams that these commercial images procure in us are very real, one can question the genuineness of the promises of betterment they present. On the other hand, the traditional performing arts such as dance, music, and theatre have added magic and wonder to our lives since the beginning of our existence as a species. These arts have no need for ILM special effects but derive their power from the sheer intensity of real human presence and the ingenuity of our own creativity. They can get us excited about reality within reality itself and in turn, connect us to a specific community, history, spirituality, and culture. As Pt. Birju Maharaj explains:

“I do not desire for human beings to become like machines that move and do without sentiment, rather every limb from our feet to our fingers should be filled with thought and emotion. I do not spend myself on anything barring the dance. I wish to create an atmosphere that aims at bringing back to dance all the sensitivity, and delicate aesthetics, which are threatened in this age of violence. Art has to exult and elevate.” – Maharaj ji

In Maharaj ji’s world of classical Indian music and dance, the linear Western clock time stands still to Taal’s infinite rhythmic cycle, the Sur, or musical notes, fills the empty space with moods and colors, while Braj Basha and Urdu poetry reign as English takes a backseat to Thumris, Bhajans, Kavitas, and Ghazals. This world further unraveled itself for the Lucknow Observer through a series interviews with the Maestro in collaboration with my work as Kathak student and performer, in order to find out what aesthetic principles put the Lucknow in Kathak’s Lucknow Gharana. We ask you, apart from the technical details, as Lucknowites, can you identity with some of these words?

- Khubsurti or prioritization of overall aesthetic presentation – from the careful placing of the each finger, to body angling for symmetry and Sajavat or decorative stylizations in design or dynamics to movements, expressions, and rhythms.

- Mithaas or the subtle, gentle, and graceful demeanor expressed through overall pleasantness and dominance of sringaar, or the romantic ras, as depicted through kasak-masak, wrist and chest movements, or nazakat, delicacy of face and neck movements.

- Nikaas or the clean finishing of positions such as paon ka nikaas where the shifting of foot positions are performed for different ghungroo sound effects, complimenting the changing of bols or mnemonic rhythmic syllables.

- Raaz or the notion that what is partially hidden is more appealing than what is fully revealed, such as the gesture of the ghunghat or the veil to hide the face.

- Ganga Yamuni Tehzeeb or the variety in both Hindu devotional and secular Mughal repertoire, for example, the ability for a performer to choose between either the Guru Vandana, invocation of Brahma, Vishnu, and Maheshwara, or a Salaami, dance aadaab salutation, as an initatiave dance, depending on one’s choice of solo performance

By discerning the aspects of the Lucknow style, we are not reviving the past but investigating the present. By understanding the value of what we have now, we can continue to imbibe what we consider to be the best in us. Unfortunately, the heavy adjectives of traditional and classical attached to these forms often create a cryptic aura of inaccessibility around them. On the contrary, traditional art is only a structure to the extent to which it can enable us to be more expressive. This process occurs through a fascinating osmosis where societal elements are absorbed by the artist which then get filtered through their personalities during practice and performance. Clear examples of the relationship between people, art, and society are many – such as the outburst of revolutionary Bebop jazz music after the 1930’s Harlem renaissance in New York or the emergence of Butoh dance after the advent of the first nuclear bombing in Japan during World War II.

Since the very creation of India as a nation, arts and especially classical music and dances have always been propagated as symbols of culture. A straightforward case is the spread of Pt. Bhimsen Joshi’s Mile Sur Mera Tumhara which helped integrate the nation under the PM Rajiv Gandhi. In this way, the performing arts, their practitioners, and institutions have managed to survive as living, moving reminders of what we value and what distinguishes us. Born only a few years before independence, Maharaj ji came at such a serendipitous time when India was in dire need of this type of representation. The seventh generation royal court Kathak dancer become proof of India’s exquisiteness, not to speak of Lucknow’s glory. Behind all of this always also remained his supportive mother Mahadevi ji who encouraged him to maintain the honor of his forefathers’ art form. Thus, fate fashioned this pioneer that had the courage to go forward so that today we can all go back and pick up the pieces of our art’s identity. Think about it this way: even if the colonials took away the Kohinoor diamond, they could not take away this country’s true richness, which continues to be protected safely within the infinite crafts of its great artists.

All in all, Lucknow is lucky not because destiny chose this individual as its artistic representative, but because this particular persona fulfilled that role with a dedication and skill greater than anyone could have ever imagined. And just like a true Lucknowite, Maharaj ji remains faithful to his roots all the while: In reference to an upcoming visit during his interview, he confessed, “…aur bare pyar se jaunga kyon ki Luckow hai, Lucknow hai, mera…” (…and I will go with much love to Lucknow because it’s Lucknow, my Lucknow…)

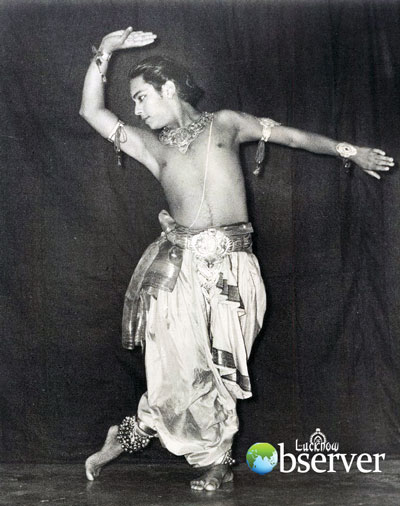

To speak of his Lucknow roots, Brij Mohan Maharaj, who now carries the title Padmavisbhushan, is from Golaganj, now known as Mishra Bandhu Marg. Though he no longer resides here, there is no doubt that he wears the grace of his city proudly wherever his dancing feet take him. The majestic movements, glistening gazes, delicate demeanor, and flawless footwork give audiences a glimpse into another world where the details matter aka Lucknow. However, to even begin to recognize the story of this Kathakaar (Hindi word for traditional storyteller), we must go to where most of the best stories often begin: the village. Originally a Mishra, an artist community largely based in U.P, today’s Kichkila gaon in Handia, Allahabad district, still has a pond and a tree as markers for the birthplace of Maharaj ji’s Kathakaar lineage. One day in the early 1800’s, Durga Prasad and his brothers, Pt. Birju Maharaj ji’s great grandfathers, received a royal command from the Lucknow court to become the official artists for the Nawab. With only a fraction of the 989 houses identified Kathak families, the ancestors of Pt. Birju Maharaj came from village to city to contribute to one of the greatest artistic renaissances North India ever saw before colonial rule. As a court artist, one of the sons of Durga Prasad, Bindadin Maharaj went on to becoming a favorite of Wajid Ali Shah’s due to his rhythmic dexterity and literary contributions to the art of Thumri. Subsequently, his three nephews also lived up to this legacy: Maharaj ji’s father, the eldest, Pt. Acchan Maharaj, became the preferred performer for several Indian royal courts including the Raighar darbar; the youngest, Pt. Shambu Maharaj became this nation’s first dance institution’s head Guru in Delhi; and the second nephew, Pt. Lachchu Maharaj became a famous film dance choreographer for many of the timeless Bollywood classics including Pakeezah, Mughal-e-Azam, and many more. Finally, when it came time for our generation’s Brij Mohan Maharaj to become the next torchbearer of the Lucknow gharana, never did he imagine that he would ever have to leave this city someday. Due to his father’s premature passing, his family’s necessity, and his uncle’s Pt. Shambu Maharaj ji’s calling to work at Bharatiya Kala Kendra, life took the young Birju Maharaj away to Delhi where he eventually would become the director of the national institute, Kathak Kendra for several decades. His transfer to the capitol and several tours abroad resulted in a long life of successes in transforming Kathak dance into the complete form it is today, as well as popularizing it as a global art form. At the age of seventy-five, Pt. Birju Maharaj continues to strive for excellence not only from himself but also from his students – performing and teaching with more vigor than ever! A multitude of admirable biographies and documentaries have been made on his life describing the steps of his journey as a Master artist, including the most recent publication by his senior most disciple Saswati Sen, entitled The Master Through My Eyes.

Today, Kathak dance flourishes internationally, from the most grand performing arts venues in large-scale choreographies to private lessons in the studio of an NRI’s home. Yet, as this form spreads farther and farther from its birthplace, new questions arise, such as, “What happens when a traditional art gets transposed to another place and culture?” As German contemporary choreogapher Pina Baush, once said, “To understand what I am saying, you have to believe that dance is something other than technique. We forget where the movements come from. They are born from life.” Such advice gives us the key to realizing Maharaj ji’s brilliance and how to go forward ourselves. As much as both Western modern dancer Pina and Indian classical dancer Maharaj ji were greatly influenced by everything and everyone that came before them and surrounded them, they were also driven by a ceaseless desire to communicate and connect with life. The only difference being that while Pina communicated individual inner feelings, Maharaj ji communicates a place and a people.

Among the multitude of Pt. Birju Maharaj’s stylistic contributions to the art form, other major innovations in the field of Indian classical art are the establishment of the solo format, beginning with a Vandana or Thaat, followed by Tihai, Tukda or Paran and finally ending with an Abhinaya, Tarana, or Yugal Bandi; the introduction of rhythmic compositions to the Thumri; the advancement of the Tihai, from a small short repetitive composition to an independent presentable rhythmic piece; and finally, the usage of modern metaphors to enable the new generations to connect to age-old stories. One wonders what would have been the fate of Kathak without Maharaj ji’s innovative zeal? Most probably it would have suffered the fate of many of today’s endangered Indian arts and definitely would not have become the known term it is today. Students and performers of this generation can attest to the overwhelming splendor of the heritage Maharaj ji teaches and performs to enrich their lives with Taal, Hastak, and Bhav. At the same time, new generation performers have also inherited a sense that they can only attempt to be imitations of an original that once was and could never again be. On the contrary, as a new generation artist, I hope that rather than giving in to the allure of nostalgia, Maharaj ji can be a beacon in our perseverant search for fresh ideas. Such an icon prompts us to perform our duty of discovering what it is the ancestors and the art are trying to say through us.

For more than a decade, Maharaj ji has now finally been accomplishing the dream of every artist by starting his own academy called Kalashram, which is based in Delhi. This institute trains young dancers in the tradition as well as puts on productions to represent Kathak dance not only as a craft but also as a contribution to society, uplifting, and nurturing those in our day-to-day lives through art. Derived from the word kala, or art, and ashram, or place of sanctuary, his institution promotes the belief that art can be a form self-discovery through duty and devotion. In addition, his most recent invitations to work closely with the film industry attest to Bollywood’s growing attraction to classical authenticity, including his choreographies in 2002 Devdas, 2013 Vishwaroopam, and this year’s Dedh Ishqiya. In the face of this performing art and its legacy, filmmakers and actors alike always put their glamor a side to pay their respects to the artist. As Madhuri Dixit exclaimed once on her show, “Many are my fans but I am the fan of only one: Maharaj ji.”

The good news for Lucknow is that your townsman is planning on coming soon to over see the government plans to convert his Mishra Bandhu Marg childhood home into a Kathak performing arts center space as well as an interactive multimedia museum. This antique haweli style home was a gift by the Nawabs to his ancestors as inaam, or reward. Though, permission has already been granted for its restoration, delays in its implementation are still a concern. These are the moments when we hope the attitude towards art gets its urgently needed makeover – to not to be thought of as an extra special activity or surplus endeavor but to be regarded as a necessity and an integral part of the human experience. Behind all the fervent patriotism and political preaching, let’s get to know the India that we say we love so much. This country’s performing arts gives us the tools to understand and explore what we have in common and a platform to share our collective, historical, and spiritual wisdom, both as individuals and as members of a greater community.

So the next time you instinctively switch on the computer, phone, or the TV to desire for something far and foreign, take a moment to think of how the world never ceases to be mesmerized by you, your own classical music and dances. Do not hesitate to look for what arts surround you or what arts you can learn and create, instead of waiting for the arts to come to you! Let’s hope that we, the artists, will always be here for you with the sweet sound of our ghungroos, the gentle tremor of our aalaap, the sparkle of our tabla, and the moving melodies of our nagma calling upon the divine.

Long live Maharaj ji and long live Kathak for they are yours, truly! Be proud of it!

Writer is from US. She is student of Pandit Birju Maharaj and Kathak is her zeal

(Published in The Lucknow Observer, Volume 1 Issue 8, Dated 05 November 2015)