The Partition of 1947

At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom…”, these unforgettable words of Pandit Nehru at the midnight session of the INC in Delhi beam with optimism, hope vested in a new beginning, and most of all, joy of a new birth, rebirth of a nation- India. While these words rejoiced the rejuvenation of the Indian freedom, liberty and independence, another nation was already in the process of rejoicing it. India’s fragmented neighbour, Pakistan, might not have heard Nehru’s speech amidst the happy noise. More than neighbours, India and Pakistan were twins, fraternal twins who didn’t look like each other, fought bitterly with one another and were separated by minutes during birth; India and Pakistan were separated by a day during their rebirths. Did they achieve in all these years what these two nations had hoped to, one may not say. But what one can easily be acquainted with is the huge price they had to give- land, power, and lives. The partition of India is a blemish on an otherwise successful rally for freedom. This view of the Indian independence is so dark that it hardly finds a statistical mention in children’s textbooks. But this dark history is not just a few lines, a paragraph or a couple of numbers. It had prodigiously grown on the minds of the people and fed on their hatred. At the occasion of Independence Day, when the world salutes the Tricolor, we might as well confront the uncomfortable face of our history and look back to what led to such great genocide, a massacre on such a large scale.

There was a huge uproar and protest from the INC against the British efforts of division of Bengal on religious grounds in 1905. This instilled a resentful feeling in the minds of resident Indian Muslims and they came to believe that the INC would always come in the way to achieve an independent Muslim mechanism. Thus, the Muslim League was formed to safeguard the interests of the Muslims.

Though the origin of the Muslim League was anti-Congress and the British tried to turn the INC and the Muslim League against one another and neutralize each other, things usually went the other way. The two factions of the Indian politics usually worked in full cooperation and laid emphasis on the notion that the British should “Quit India”.

It was a common agreement between the INC and the League to deploy voluntary troops in the First World War and fight on behalf of Britain. Anticipations were that Britain would provide political relief in return of the service of over 1 million Indian men, including independence. But there were no such offers or proposals put forward by the British. Then came the Second World War, and the relations between the Congress, the League and the British became even more tensed. The British were in bad need of the Indian men and materials to brace themselves for the war. But the INC, being once betrayed by the British during the First World War, did not want to involve the Indian soldiers in another futile bloodbath. The Congress just wasn’t up to let the Indian men fight Britain’s war in vain. However, the Muslim League decided to respond to the British distress call with an affirmation. This was probably an attempt to gain extra favors from the British and get a nod from them for the formation an independent Muslim nation in what was to be Northern India after Independence.

It was a common agreement between the INC and the League to deploy voluntary troops in the First World War and fight on behalf of Britain. Anticipations were that Britain would provide political relief in return of the service of over 1 million Indian men, including independence. But there were no such offers or proposals put forward by the British. Then came the Second World War, and the relations between the Congress, the League and the British became even more tensed. The British were in bad need of the Indian men and materials to brace themselves for the war. But the INC, being once betrayed by the British during the First World War, did not want to involve the Indian soldiers in another futile bloodbath. The Congress just wasn’t up to let the Indian men fight Britain’s war in vain. However, the Muslim League decided to respond to the British distress call with an affirmation. This was probably an attempt to gain extra favors from the British and get a nod from them for the formation an independent Muslim nation in what was to be Northern India after Independence.

During the 30s, Mahatma Gandhi emerged as the leading power in the INC. Gandhi always dreamt of, and endeavored for a united India with equal rights being given to both Hindus and Muslims. However, other members of the Congress were not so enthusiastic about collaborating with the Muslims in the fight against the British. This increased the hostility between Hindus and Muslims and eventually, the League started making further endeavours for an independent Muslim state. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was the leader of the Muslim League, started campaigning publicly for an independent Muslim nation, and on the other side, Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru demanded a unified India.

In 1945, Labour Party was voted-in in England that supported the Independence propaganda and issued immediate independence. As the hour of freedom came nearer and nearer, the nation started to descend towards a religious civil war. Gandhi tried his best to bind the people in a peaceful protest against the British, but failed. Muslim League called for a “Direct Action Day” on 16th August, 1946. More than 4000 Hindus and Sikhs were killed in Calcutta that day. And thus began the “Week of the Long Knives”, a murderous festival that took a toll on countless lives in various cities across the country- both the Hindus and Sikhs, and the Muslims.

The British Administration, in February 1947, declared that India would be handed over her freedom by June of 1948. Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Viceroy of India, tried to reason with the two factions and tried to convince them to form a united nation, but could not succeed. The only support he saw was the one coming from Gandhi. Seeing the already critical condition of the country, with the increasing violence and killing all around, Mountbatten finally succumbed to the demands of two separate nations, and moved the date of independence up to 15th August, 1947.

The British Administration, in February 1947, declared that India would be handed over her freedom by June of 1948. Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Viceroy of India, tried to reason with the two factions and tried to convince them to form a united nation, but could not succeed. The only support he saw was the one coming from Gandhi. Seeing the already critical condition of the country, with the increasing violence and killing all around, Mountbatten finally succumbed to the demands of two separate nations, and moved the date of independence up to 15th August, 1947.

Once the decision of partitioning was given consent, the two parties now had the mammoth task of fixing borders between the two nations at hand. The Muslim occupied regions lied on the opposite side of the country, with a vast ocean of Hindus separating them. Also, in Northern India, the population was a blend of the two faiths, notwithstanding Sikhs, Christians and other minority religions. The Sikhs rallied for a separate nation as well, but their appeals were put down.

In Punjab, the situation was more dire than the remainder of the country, with an evenly mixed populace of Hindus and Muslims. Neither party wanted to give up this precious state, and the sectarian discord rose higher. The border had to be drawn right through the middle of Punjab.

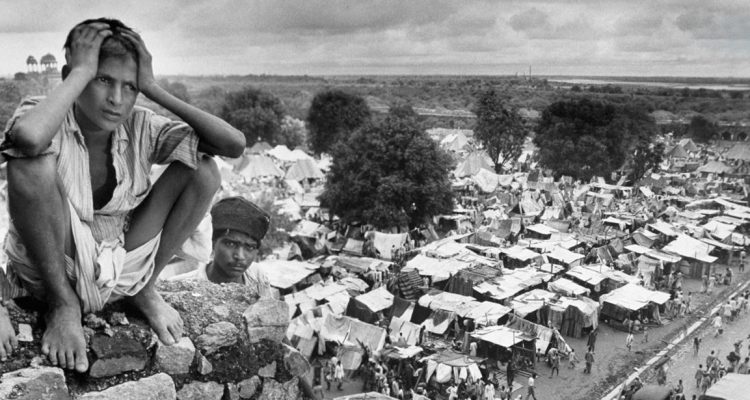

After the borders were fixed, the people hurried off to get to the side of the border where they belonged, where their faith allowed them to be. They either migrated willingly, or were chased from their homes. At least 10 million people had to migrate on either side of the border and more than 5 lakh people were killed in the riots that took place during the partition. Trains that carried immigrants and refugees were assaulted or set on fire from both ends, killing everyone on board.

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan was formed on 14th August, 1947. The Republic of India was formed a day later, on 15th August, 1947. And thus, India was partitioned.

Not only land but also various assets such as the army, administrative services, the treasury and the railways were subjected to division.

The riots during the partition took the shape of genocide. The riots took place in the Punjab region, and 2-5 lakh people lost their lives. According to UNHCR, this was the largest incident of mass migration in the history of mankind, with an estimated number of 14 million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs displaced.

The population of pre-independence India in 1947 was nearly 390 million. Of these, 30 million went to East Pakistan and almost 30 million to West Pakistan, leaving around 330 million people in the post-partition India. After the borders were decided, about 14.5 million people switched to either side hoping for safety and security.

According to the 1951 Census of Pakistan, a total of 7,226,600 people were displaced into Pakistan from India. Also, the 1951 Census of India stated that 7,295,870 people were displaced into India from Pakistan. These numbers sum up to a staggering total of 14.5 million displaced people. The two censuses were conducted after 3.5 years of Independence and took into account, the increase in population of the region after the mass mobilisation.

According to the 1951 Census of Pakistan, a total of 7,226,600 people were displaced into Pakistan from India. Also, the 1951 Census of India stated that 7,295,870 people were displaced into India from Pakistan. These numbers sum up to a staggering total of 14.5 million displaced people. The two censuses were conducted after 3.5 years of Independence and took into account, the increase in population of the region after the mass mobilisation.

The governments on both sides had no idea how to handle such a huge wave of immigrants; the violence and killings on both sides of the border became horrendous. About a million people in all were killed in the panic and outrageous baffling. Women were delivered with crimes much more heinous than murder- they were raped, gang raped and tortured, and then murdered in most of the cases. With these riots, human monstrosity stooped to an all new low which is probably unparalleled in the history of mankind, all because of a decision made by the people sitting miles away from the heat people faced in ground reality.

Punjab and Bengal were the most influenced areas where people found an excuse to unleash the animal in them and indulge in utterly horrid crimes- people from Hindu, Muslim and Sikh community.

Punjab, Bengal And Sindh

The Boundary Commission faced great challenges while deciding which way Lahore and Amritsar should go. Ultimately it was decided that Lahore would be given to Pakistan, and Amritsar to India. There were a large number Hindus and Sikhs in certain areas of Western Punjab that also included Lahore, Rawalpindi, Multan etc., and also in Gujarat. Similarly, Amritsar, Ludhiana, Gurdaspur, Jalandhar and other cities in East Punjab had a large Muslim population. These populations in the “wrong” part of the land ended up being assaulted and killed.

Bengal was dealt with a fate similar to Punjab when it was divided into West Bengal which belonged to India and East Bengal to Pakistan. East Pakistan later became an independent entity by the name of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

Bengal was dealt with a fate similar to Punjab when it was divided into West Bengal which belonged to India and East Bengal to Pakistan. East Pakistan later became an independent entity by the name of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

While districts like Murshidabad and Malda, that were Muslim majority, vested to India, the rarely populated Buddhist majority Chittagong Hill Tracts was given to Pakistan by the Radcliffe Award.

It was expected that Hindu Sindhis would stay in Sindh after the partition, in light of the fact that Hindu and Muslim Sindhis had maintained comparative harmony with each other. Approximately 1,400,000 Hindu Sindhis thronged the cities like Hyderabad, Karachi, Shikarpur, and Sukkur, at the time of Partition. But, there hovered on their future, an uncertainty while being in a newly formed Muslim state. Also, there were better prospects of opportunities in India, but the biggest factor was the immense inflow of Muslim refugees from Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajputana (Rajasthan) and other parts of India that would have reduced them to a much smaller minority than they already were. Hence, they saw it only fit to move to India.

Resettlement Of Refugees In India : 1947-1957

Like the Sindhis, the Hindu Punjabis and Sikhs in West Punjab fled from there and settled in India occupied East Punjab and Delhi. Not only West Pakistan, but a similar fleeing of Hindus was seen in East Pakistan as well that got settled in Assam, West Bengal and Tripura. For a single city, Delhi got the largest refugee influx. Delhi’s population saw a dramatic rise in 1947, and the net population almost doubled between 1941 & 1951- from 917,939 to 1,744,072. These refugees were sheltered in military and historical accommodation such as Purana Qila, Red Fort, and military barracks in Kingsway Camp(around the present Delhi University). Kingsway Camp barracks soon turned into North India’s largest refugee camps with over 30,000 refugees, along with Kurukshetra camp in Panipat. Starting from 1948, the Government of India undertook building projects to convert these campsites into permanent dwellings. Lajpat Nagar, Rajinder Nagar, Nizamuddin East, Punjabi Bagh, Reghar Pura, Jangpura, Kingsway Camp and many other colonies in Delhi emerged during this period.

Resettlement Of Refugees In Pakistan : 1947-1957

Pakistan, on the other hand, had the same story to tell. People from neighbouring Indian states like Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh made up the larger part of the migrants settling in West Punjab, while also including migrants from Jammu & Kashmir and Rajasthan. Sindh saw the advent of migrants from Urdu-speaking background (called the Muhajirs) and came from the northern and central urban centres of India, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan through Munabao and Wagah borders.

Throughout the ’50s, the Muhajirs spread across Sindh in cities like Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Nawabshah and Mirpurkhas. Some of these Urdu-speaking gentry even settled in Punjab in cities like Lahore, Multan, Bahawalpur and Rawalpindi. Sindh was estimated to have received a total of 1,167,000 migrants, of which, 617,000 migrants converged in Karachi alone. From 400,000 in 1947, Karachi almost tripled its population to 1.3 million in 1953.

As the time passed, people, both residents and migrants, blended in their newfound society and soon became so homogeneously mixed that no one could tell one from the other. Gradually, the new generation replaced them and the memory became a scarcity. But there are still survivors, who have given their account of the partition, on borders as well as in the cities. Here is how they describe it.

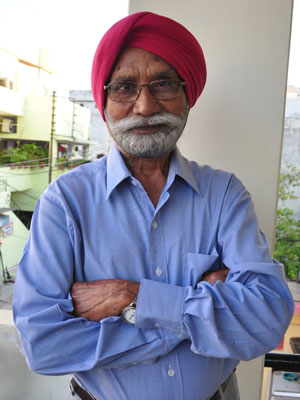

UJAGAR SINGH

What I have received from my parents is that in those times, the Muslim population had started believing that the land, which now lies with Pakistan, belonged to them and the non-Muslims cannot stay there any longer, way before the declaration of the Partition. For instance, the kids would enter into a fight and a Muslim kid would taunt the non-Muslim kid over them being thrown out of their own houses.

I remember an incident, my uncle, Nihal Singh, decided to stay. He was adamant that we shall not fall prey to the British tactics. He was one of the stout healthy members of our family, and insisted that he had his Hindu brothers with him and the people here would not kill him. He did not come. In the violence, prior to the Partition, he, along with his entire family, was killed.

As far as my family was concerned, we staggered from place to place before we could unite. There was nothing to eat, nothing to drink. Our clothes were torn and we were exhausted. The most the people could do was to bundle up their ornaments and tie them in a knot. What else could they carry anyway? They had to move to different places without knowing when this would stop. Those who came by train had to face violence as well.

Another great tragedy that not only me but almost everyone who migrated from Pakistan (proposed) had to suffer was that they couldn’t unite with the people they once parted. They went to places, where they could find space, find an availability of amnesties.

If we had a distant relative with a business, job or any commercial sustenance in India, he became our last resort for a haven. Apart from the farms and cattle, our ladies, too, indulged themselves in domestic cottage industries and weaved sheets called Khees. It had a market here in Uttar Pradesh near Faizabad. My father used to travel to Khajrawat here and stay there for months. Upon entering India, we first went there while my father’s elder brother moved towards Bihar. And in this way, families split and once they did, they found it really hard to unite again.

We were called ‘refugees’ at that time, despite being from the very same country. Just because a line was drawn on paper, one was a refugee, an alien in one’s own country. Even though we migrated before Pakistan was formed, we were labeled refugees. The government schemed to provide aids to these ‘refugees’ but not everyone got them. And the aids were insufficient- the land provided for cultivation turned out to be barren, the area issued to the people were way less than what they had and thus, could not sufficiently go about with their livelihood. The migrants spread across the whole country, struggled for their survival; some made it while others couldn’t.

JOGINDER SINGH

I had my home in Anandgarh village in district Sialkot, which is now in Pakistan. In 1946, I went to my sister’s house in Haldwari village; district Lailpur during my summer vacations. I stayed there for a few days, but before I could fully enjoy my vacations, the orders for the Partition of India were passed and a wave of egregious violence drowned the entire atmosphere.

One day, the Muslims of that area surrounded the village. They shot fires. They had all kinds of weapons. We sat helplessly inside as their siege of the village continued. Some strong men of our village decided to confront them to stop them from entering the village, but the invaders outnumbered them. They were about to enter our village when the military arrived and started firing at them. We were saved by the military intervention. They camped in our village for a few days lest the Muslim rioters should attack again.

It so happened that our military was held captive by the opposition military. Yes, even the military was divided into two factions of Muslims and Non-Muslims. A man escaped from their captivity and came to our village, and told us that the rioters are going to attack the village again as this time, we won’t have the military on our side. He asked us to abandon the village overnight. We took all the small stuff we could in our hands.

Our trucks were stopped at Lahore and not allowed to enter India. The incharge there must have had thought of setting us up for massacre by the Muslim mob. It had happened many times before too. In fact, the trucks carrying refugees from either side were turned into vehicles loaded with mutilated corpses. We were afraid for our well-being, but our military men asked us to remain calm and stay inside the truck while they’d talk it out. They approached the diplomacy there, and the people from the commissioners’ offices posted in Lahore. They finally succeeded in geting an order issued to let us pass. We breathed a sigh of relief when we finally crossed the Ataari Border. We safely reached Amritsar, and when we got off the truck, my sister and me searched for our parents. It was a long struggle but we finally found each other. We stayed in Amritsar for a while. I had a brother who worked for the Railways in Dera Baba Nanak and got posted in Lucknow. From there started my life in Lucknow, my early days spent in tents and camps and things gradually got better.

KRIPAL SINGH

At the time of partition, I was 16 years old. My father was a serviceman there while I was a student. My village lied in district Shekhupura. We had our own farms. I studied in Lahore.

The British ordered the day of our freedom to be August 15th.

On that very day, hell broke lose between the Sikhs and the Muslims. There was a meeting in the Assembly Hall in Lahore. In that meeting, the Muslims hoisted Pakistani flag. This enraged Martyr Tara Singh, leader of the Sikhs, and he got up and cut off the flag with his sword. The reward for Tara Singh’s head was set at Rs.25, and Rs.10 for a Hindu head each. We turned back to our lands at Shekhupura instead of fleeing to Amritsar.

We were attacked by a combined force of Muslims from Multan, Lahore and Montgomery, but the people in the camps faced them bravely and they had to retreat. There wasn’t much damage done to us. The crusaders though, suffered thrice as much as we did. This created a lot of buzz and later on, a unit of the military was sent to evacuate the camp. We already had around 25-30 soldiers but they couldn’t do much without our help in front of such a huge crowd of wreckers. Trucks were provided for our transportation, and men were asked to stay back while women and children would be deported first.

We reached Lahore. A special collected infantry was deployed there solely for the protection of Hindus and Sikhs. There they arranged for us the Military Special train at Mianmeer Station. But the guard and the driver decided to trick us. When we boarded the train, they said that they were bringing the train on the other platform, but made off without the military. The military was left behind at the station while we were left unguarded in the train.

The train halted at Kasur station and within a few minutes, the platform was packed with angry seething Muslim men. It was then that we realized that it was all part of a plot and we had been set up. Now, around 60-65% of the people travelling with us were retired military men. When they saw that we had been surrounded, they put on their old uniforms, stuck out the butts of their rifles and demanded, ìWhy has the train stopped?î They were careful not to expose their indigenously made rifles instead of the military commissioned 3 knot 3 English ones. With some courage, they even got down on the platform, which intimidated the hoard to no extent and the train had to be prepared to leave the station.

When the train was about to leave, the military that we had left behind caught up with us. As soon as they saw the crowd, they threatened it to back off or else there won’t be a single soul leaving the station alive. The British officials had openly said that if anyone touched our family, we should raze the station to the ground and they’d handle the rest.

When we proceeded towards Ferozepur, the next station was full of Hindu people who were removed from the train that departed before ours. It was told to them that the train they were travelling in was Pakistan special and had even been fired at, though not much damage was incurred. They had Gorkha Regiment with them. We accommodated these men and the Gorkha military in our train. People had to hang from the doors and climb up to the top of carriages. Finally, thousands of people reached Ferozepur.

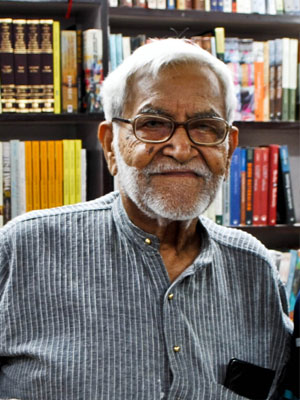

RAM ADVANI

The Partition happened in August 1947. I left Rawalpindi and then Lahore in March or April 1947 because by that time, we had gotten an idea that, things might go wrong here.

What we all knew was that it’s going to be difficult for Hindus to live in Rawalpindi or Lahore. At that time, I didn’t even know the scale at which the violence had spread. All my friends, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, were under the impression of ‘Tayyari karo jaane ki’ (be prepared to leave).

At the time of the Partition, I had just entered my 27th year, and went straight to Bishop Cotton School in Shimla. There they thought I was there to work. I had worked there earlier as a Personal Secretary during wartime. They were ready to take me as an employee when I told them that I wanted to take shelter there as an old Bishop Cotton School teacher in one of their guestrooms, and I wanted to be a bookseller.

I remember, it was in August 1947, I was near the Leela Talkies when 7-8 boys stopped me and tried to rattle me. “Badi himmat hai aapme jo aise chal rahe hain!”, one of them remarked at my audacity to roam the streets being (apparently) a Muslim. I told them that I’m a Hindu and own that bookstore in the corner at Mayfair building. When a couple of them recognized me as ‘Ram’, I was allowed to go. They were no longer hostile. I also invited them over a cup of tea. I had even heard that in the mohallas, they’d ask you to pull your pants down to verify which religion you belonged to. Thankfully, I never got to see such outrageous deeds and they stayed confined in the mohallas only. There were no big violence or riots that I might have witnessed. Whenever a clash was impending, I’d go inside and hear the noise.

There’s this incident in Bishop Cotton School in Shimla that I witnessed. One night there came a news that the 26 Muslim kids were in danger. There were nearly 360 students there. All of those boys were from well to do families. Brigadier Daulat Singh, who was known to me, phoned us and said that these kids can’t be taken by the ordinary route as there are chances of them being attacked. For this, they provided 3 army vans. The middle one would carry the boys while the front and the back vehicles would carry armed soldiers. The news followed back that the boys had safely reached the destination and all was well.

After all these years, people ask me to come and see my home. I decline, because the memory I hold of Lahore and Rawalpindi needs to be cherished. The Lahore of today, would not be the Lahore of my childhood, where I played cricket, football, marbles etc. And besides, Lucknow is my home now.

As far as the Partition is concerned, it cannot be good for me, for anyone, giving up your childhood place not knowing if you’ll ever return. Now that I think of it, I feel a little angry at myself for even hoping that we could return. But in those times, we hardly knew how the Partition would take place or what its consequences would be. But whatever it might be, it is still too early to give a verdict on the aptness or propriety of the Partition of India.

Shamim A. Aarzoo

Writer is the Editor In Chief of The Lucknow Observer & Founder of LUCKNOW Society

(Published in The Lucknow Observer, Volume 2 Issue 17, Dated 05 August 2015)